While it perceives itself as one of the most sexually liberal nations in the world, the Netherland’s black LGBTQ community remains unseen, unheard, and underrepresented. In a new ongoing project, Curaçao photographer Dustin Thierry explores the reasons why.

The Netherlands is a very paradoxical country. It was the first place to legalise same-sex marriage, with Amsterdam being named one of the most LGBTQ-friendly cities of the world.

However, the Netherlands also has a complicated relationship with race. People of colour are poorly represented in the media, in politics, and in the arts. Black history and colonial history are not taught in schools. The Dutch society sort of denies and distances itself from engaging with slavery and racism.

This hesitancy to engage with race allows racism to go mostly unchallenged; thus, there is no recognition of the way that this historical legacy of slavery still impacts and shapes the lives of black people in the Netherlands today.

I’m currently based in the Netherlands – but I’m originally from this beautiful pebble called Curaçao, which is a small island in the Caribbean (a former colony of the of the country).

I’ve always been interested in cultural identity relating to my Caribbean roots. Back in June of 2016, my little brother took his own life as a result of ongoing mental struggles that partially had to do with his sexuality. To this day, homosexuality is strongly stigmatised and condemned within the Caribbean community. It led me to wonder; what does it mean to be gay and black in the Netherlands? And in Curaçao? Moreover, in what way do black Caribbean lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender persons give meaning to their identity?

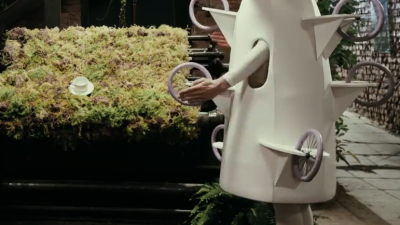

These questions ultimately led me to the Dutch Ballroom scene, a form of expression where all these cultural elements come together. I began to understand that my photography could amplify the voice of the Ballroom scene because in a way I could see myself in it. My blackness, my search for artistic freedom and expression, my dance and the feeling of family.

The portraits I took of the Dutch ballroom scene are part of a broader long-term project to document black queer subcultures in the Netherlands, made with cultural anthropologist Wigbertson Julian Isenia (University of Amsterdam). We want to contest the very dominant image of the Netherlands being exclusively white, removed from its colonial history and (former) colonies and its essentialist (European) perspective on gender and sexuality.

Ultimately, we contend that homosexuality and gender performance are conceived differently in multiple cultural contexts. We hope that, through photography and visual research, we can bring (more) justice, acceptance and knowledge.

Comments