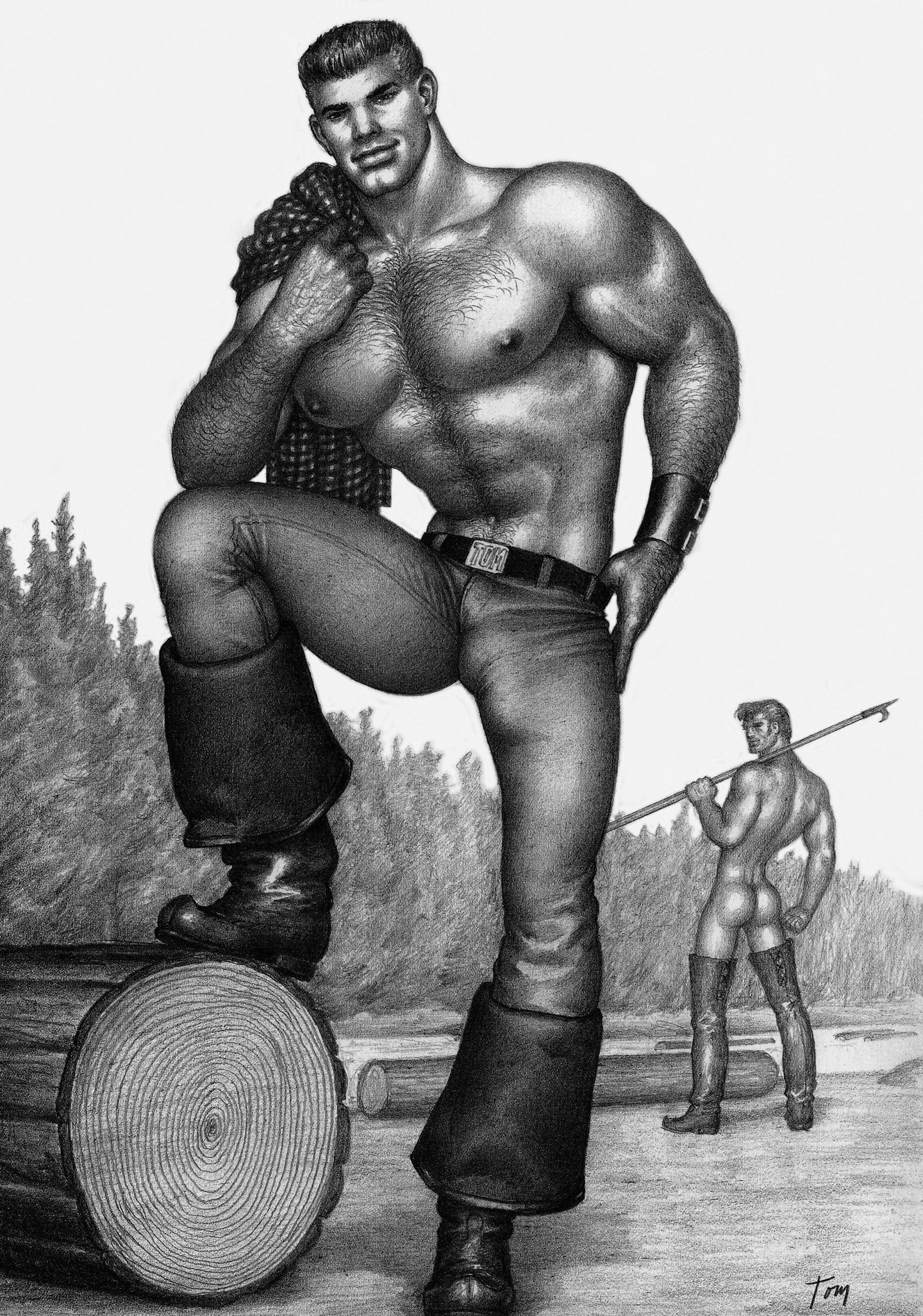

As a biopic about the beefcake trailblazer hits theatres, we explore the legacy of the Finnish erotic artist with the film’s director

About halfway into the new Tom of Finland biopic, there’s a poolside scene that perfectly encapsulates the exhilaration experienced by iconic, provocative Scandinavian artist Touko Laaksonen (his real name) upon first setting foot in California. It’s the late 1970s, and Tom/Touko has just been acquainted with his number one fan (and future business partner) Durk Dehner, as the SoCal sexual revolution is in full bloom. “Kid in a candy store” doesn’t come close to describing Touko’s glee as he snaps pictures of men in leather chest harnesses and others in snug-fitting swim trunks whacking away at each other with inflatable penises. When the local police storm the party, Touko assumes it’s a morality raid akin to what he’s known in Helsinki, where LGBTQ peers and friends would get locked up for the simple act of congregating.

But when the uniformed men (a focal point of Tom’s beefcake erotica) explain they’re looking for a mini-market robbery suspect, before kindly wishing the partygoers well, it’s a eureka moment for Touko. It dawns on our humble homo hero that the promised land he’d been conjuring for years via illustrations of well-endowed lumberjacks, law enforcement officers and leathermen might actually exist in some capacity.

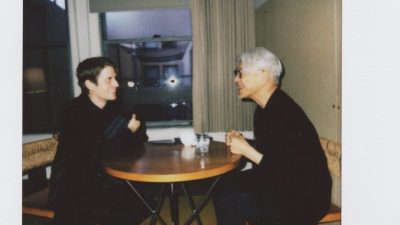

“It’s a true story,” Tom of Finland filmmaker Dome Karukoski tells me when I bring up the scene. “In reality, there were 20 cops who showed up to the party, but we could only afford 8. All of the craziest things we depict in the film actually happened. His life was so cinematic and crazy that we didn’t even need to focus on his drawings. That’s what struck me most after five years researching him.”

He has a point. While the famed homoerotic artist’s 3,500+ illustrations helped fuel the 1970s gay liberation movement as well as an international leather scene, Karukoski’s biopic looks beyond his transgressive art to explore the life of a mysterious and unconventional hero. From Touko’s time as a second lieutenant during the Second World War and his career as a successful art director in advertising to his longstanding relationship with partner Veli, at a time when gay men still risked castration and incarceration, Tom of Finland broadens our understanding of this true trailblazer. As the film continues its theatrical run in the UK, we examine the legacy of Touko’s signature square-jawed, unusually beefy and super-phallic fantasy men with Finnish director Dome Karukoski.

ONCE REGARDED WITH SHAME BY FINNS, HE’S NOW A SOURCE OF NATIONAL PRIDE

Karukoski was but a teenager when Laaksonen passed away of emphysema in 1991 and was revealed to be Finnish. “I remember there was a national sense of shame that this person was Finnish,” he recalls. “Like, ‘now everyone in America and Australia will think we’re leather gays with big dicks.’ It continued until recently, when the national conscience shifted to being proud of him. It has taken many, many years to change how we view him and his art.”

While Finland didn’t decriminalise sex between men until 1971, the country has indeed orchestrated quite the about-face over the last decade. In 2014, their postal service embraced its once-ostracised sexual pioneer by way of commemorative stamps (of record-breaking popularity, and which Russia tried to ban, obviously). This year, the country legalised same-sex marriage, named a “national” emoji in honour of TOF and made Karukoski’s biopic a serious box-office smash. “It has changed tremendously in the last 5 years. I think the main reason for that is the government stance. It was such a scandal in 2014 that we as a nation were officially recognising him; the Conservatives were so against it. I remember ridiculous comments about how we should give the stamp to a war veteran instead, not realising Tom of Finland was, in fact, a war veteran.”

GENERATIONS OF MEN LEARNED TO EMBRACE THEIR DESIRES THROUGH HIS ILLUSTRATIONS

Shame around same-sex desire was the watchword when Tom’s homoerotic illustrations were first published in American magazine Physique Pictorial in the late 1950s, as censors forbade depictions of “overt homosexual acts.” As courts gradually loosened their prudish grip, what continued to set Tom’s drawings apart (beyond the BDSM, bulging biceps and generous genitalia) was the unwaveringly confidence of his characters.

“Tom of Finland characters are always smiling; they carry no shame about their sexuality, fetishes or fantasies,” reasons Karukoski. “It’s about joy. I think turning sex into a joyful experience is something that still affects people in 2017. You don’t have to be in Chechnya to experience the liberation it provides. This idea that whatever your fantasies are, they’re okay, as long as people are with it and are having fun with you. With (screenwriter) Aleksi Bardy, we wanted to make a film where the audience would leave the cinema wanting to dance, love, have sex and enjoy their lives to the fullest. We wanted the film to express what Tom was conveying through his art.”

“Tom of Finland very intentionally drew gay men differently than how society perceived them” – Dome Karukoski

HE’S REMEMBERED AS A CLARK KENT-ESQUE SUPERHERO WHO LED A DOUBLE LIFE

When Touko is caught red-handed in Berlin with what was considered a filthy man-on-man doodle, the film illustrates how he learns stealth is the only way to keep doing what he does. The friend he calls on to bail him out offers a sobering warning: “It’s not just a piece of paper. It’s an atomic bomb. You could go to prison for that. The police will search your house – and interrogate family and colleagues.”

Yet Tom continued to demonstrate tremendous resolve in leading a double life according to the classic superhero blueprint. “Clark Kent and Superman is a particularly fitting comparison, as TOF could work in an ad agency wearing a tweed suit one minute, then hop into a limousine the next and put his leather gear on,” remarks Karukoski. “He’d arrive at JFK airport and a limo would be waiting with his leather gear inside. There was a guy holding a gin & tonic for him. We tried to make that scene as close as possible to real life.”

HE COMPLETELY TORE DOWN THE CORRELATION BETWEEN GAY MEN AND WEAKNESS

“My whole life, I have done nothing but interpret my dreams of ultimate masculinity, and draw them,” Touko once summed up. While we now call out (and justifiably so) a mainstream gay culture that too often rewards men for “masc” or “straight-acting” behaviour – pointing to the inherent homophobia and misogyny wrapped up in such judgment calls – Tom of Finland’s macho illustrations of moustachioed bikers and buff, boot-clad hunks were among the first representations of gay men to challenge the prevailing “pansy” stereotypes of the time. Finnish medicine manuals back then even seemed to suggest gay men had lower testosterone levels, Karukoski tells me.

“During research, I met a butchy guy in L.A. who told me he was a quarterback in North Carolina growing up,” says Karukoski. “He had these erotic thoughts but never thought he could be gay. Then he saw Tom’s artwork and understood, based on the drawings, that he in fact could be. So he immediately left for L.A. and has been living there for 40+ years. Tom was part of a group of artists who embodied the Santa Monica phenomenon, where gay men pumped themselves up at Muscle Beach to become something other than the stereotype of the flamboyant gay man. TOF very intentionally drew gay men differently than how society perceived them.”

“We wanted to make a film where the audience would leave the cinema wanting to dance, love, have sex and enjoy their lives to the fullest. We wanted the film to express what Tom was conveying through his art” – Dome Karukoski

WERE HE STILL ALIVE, HE’D BE DRAWING ISIS FIGHTERS GETTING IT ON

After Tom is detained in Berlin for possession of lewd material, as we see in the film, he begins to sketch out sexual fantasies with prison guards. The artist was always driven by a yearning to ridicule his oppressors. “He was cautious because he might get beaten, go to jail, get castrated or lobotomised, but he bore no shame nor fear,” explains Karukoski. “If the cops beat him, his next drawing would feature cops having sex in a park.”

I ask the filmmaker whether reports of The Queer Insurrection and Liberation Army fighting ISIS alongside the Kurdish army in Northern Syria is something he’d be proud of, as a former military lieutenant. “I think he’d be very happy,” he considers. “I always joke that if he made his drawings today, he’d probably draw Chechen military men. He loved that: to ridicule the people oppressing his kind. He’d also probably have made drawings of ISIS fighters having sex.”

TOUKO WOULDN’T MIND THE CORPORATE LOVE AFFAIR WITH TOM OF FINLAND ONE BIT

Finland’s embrace of their prodigal son took nearly 50 years. Another group that’s recently begun worshipping at the altar of the underground icon is corporate culture – skateboards, colognes, super-premium vodkas, coffee beans, sex toys, bedding and a capsule collection for Nicola Formichetti’s Nicopanda line have sprouted up on the market of late, all marketed with the artist’s fleshy, cheeky stamp. Would Touko be rolling over in his grave, I wonder? “No, he would be so proud,” Karukoski insists. “He worked at an ad agency for 15 years and was extremely proud of his work. The licenses to use his likeness are given out by the TOF Foundation, which is run by Tom’s great friend Durk according to Touko’s direction, one of which being to make his art visible. So whether it is in a movie, a coffee jar or on a sheet of linen, it’s continuing the legacy he wanted to keep alive. If Tom were to see a 15-year-old girl walking around the streets of Helsinki with a T-shirt emblazoned with his illustrations, I can guarantee to you, 100 percent, he’d be proud of it.”

Comments