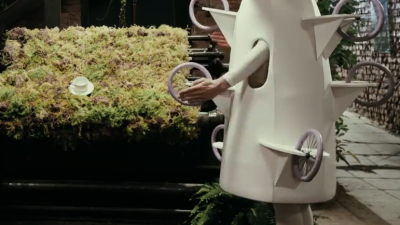

Left: Kamiko made with Mino washi. The inside is stuffed with silk cocoon, and beautiful stencil dyed patterns are featured on both the outer surface and inner lining. Right: A paper dress made as a fashion novelty during the 1960s.

Left: Kamiko made with Mino washi. The inside is stuffed with silk cocoon, and beautiful stencil dyed patterns are featured on both the outer surface and inner lining. Right: A paper dress made as a fashion novelty during the 1960s.

This disposable “paper dress” was a gift that I received from a friend who works as an antique dealer in New York. The dress was made as a fashion novelty during the 1960s, a time when a high volume of synthetic materials was being developed against the backdrop of an increase in mass production and consumption.The dress was probably created as an experimental item, and the message behind it, presumably, was that “a time was approaching where it would be possible to wear a completely new outfit everyday”.

On the other hand, a type of kimono made from washi (Japanese paper) called “kamiko” has existed in Japan from long ago. The thick sheets of washi were crumpled up and softened, and pastes made from konjac roots, persimmon juice, and agar were applied on the surface to make the paper waterproof before being made into kimonos. During the Edo period, fabrics such as cotton and fur were considered luxury items, but as washi production spread throughout the country, the lightweight yet warm kamiko became a more affordable option for everyday wear among civilian people.

0117105013006 DOTERA COAT (WASHI LIGHTNING)

0117105013026 ASCOT MORNING COAT (WASHI CHECK)

0317105008009 ELEVATION MID SKIRT (WASHI-MULTI)

On one hand there is paper clothing that was introduced during a time when material items were plentiful due to mass production, and on the other hand there were paper kimonos made during a time when fabrics were scarcer and difficult to obtain. I found the contrast between the two to be very interesting and thought that this could provide a hint for making a modern-style garment using paper.

So, for our 2017 collection, we created a jacket and skirt using handmade Mino washi. The patterns were dyed onto the paper using a traditional method used for kamiko from long ago called “kata-zurizome”.

Taking old, forgotten fabrics and reexamining them with modern conceptualization and techniques can open up new possibilities. Everyday, we repeatedly experiment to achieve this.

Mino Washi

Mino washi is known as a beautiful thin and durable type of paper. Thought to be “Japan’s oldest paper”, it boasts a history of more than 1,300 years and the oldest existing document can be traced back to the Nara period where it was used to make family registry in Taiho 2 (702 AD). Today, these original documents are preserved in the Shosoin Repository in Nara Prefecture. During the Edo period, Mino washi was used to make the official paper used by the Tokugawa shogunate, and it also became an industry standard and preserved as the official B-series paper size in Japan.

The thinness and durability of Mino washi is made using a traditional technique called nagashizuki. The washi paper is finished to a uniform thickness while being rocked right and left, and front and back inside a wooden box called a sukifune that is filled with water.

High quality Mino washi was a versatile material uses to make items like luxury shoji paper used for sliding screen doors, traditional Japanese umbrellas, and paper for transcribing sutras, but due to changes in peoples’ lifestyles after World War II, the demand for it decreased significantly.

At its peak there were over 5,000 houses with paper mills in villages neighboring the city of Mino, but today that number has been reduced to around 30. Furthermore, it was registered by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage in 2014. Today there are approximately ten artisans remaining who know how to make Hon Mino washi, considered the highest grade Mino washi.

Production Process of Mino Washi

Hakuhi (Peeling)

The bark of the Kozo branch is peeled off until only the white flesh is left.

Sarashi (Bleaching)

The bark is submerged in water and softened while removing all of the soluble materials by washing it away. Traditionally, the kozo branches were immersed in the river for up to two to three days, but today this process is more often done in man made special water baths.

Shajuku (Boiling)

To remove the fibers, the exposed kozo branches are boiled in a large kettle filled with baking soda for approximately two hours.

Chiri-tori (Removing dust)

Any dust or discolored parts from the black bark is removed by hand in cold water.

Koukai (Beating)

After all of the dust is removed the softened kozo branches are placed on a stone slab and beaten to a pulp using a wooden mallet. The fiber is flipped around several times and beaten thoroughly

Kamisuki (Paper-making)

The sticky liquid extracted from the root of Tororoaoi called “nebeshi” is mixed with the beaten kozo pulp in a large vat called a sukibune. The liquid inside the sukibune is mixed and scooped using a tool called the suketa. The suketa weighs over 20kg, so bamboo sticks fixed to the ceiling are used to support it while making the paper.

Assaku (Compression)

After the paper is made and stacked into a pile, it is placed under a press for a full day to squeeze out the moisture, adding more pressure gradually over time.

Drying

Each sheet is individually removed from the pile, pasted onto a board using a brush made out of various animal hair, and finally dried under the sun.

Sorting

Each individual piece of finished paper is inspected by hand. The paper is held up to a light, and any sheets with rips, tears, or impurities such as dust are removed. The thickness of each individual sheet of paper is also examined carefully when selecting which ones are used.

Cutting

The selected sheets of paper are cut into the appropriate size based on their application using a special knife.

The bark that can be used as raw materials can only be found in 8% of raw wood and only half of that can be used to make the paper. A piece of kozo weighing in at 100kg can only yield about 4kg of Mino washi, which takes approximately 10 days to produce. The hands of a season artisan carefully craft each and every single piece of Mino washi.

Comments