“The Woods Near the Quarry,” 2016.Photographs by Jocelyn Lee / Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery

The fifty-six-year-old photographer Jocelyn Lee has been making frank and intimate portraits for twenty-five years—of teen-agers, of teen mothers, of women of all ages and stages of life, including some near the end of it. Her process is slow and meditative; she prefers to photograph her girls and women unclothed. “I’m interested in vulnerability,” she has said, “and what arises from it.” When she recently moved to Maine from New York, though, she noticed that her new natural environment began to assert itself in her images, commanding a presence equal to that of her human subjects.

In a photograph titled “Forsythia,” from her latest series, “The Appearance of Things,” for instance, a young woman with hair dyed fiery red poses before a saturated-yellow bush. Standing in intensely bright sunlight, the girl becomes a wholly reflective object, the sun bouncing off her white shirt, which blends into her pale skin. She squints at the camera, and the viewer squints back—in the searing glare, the girl’s features are slightly blurred. While making the portrait, Lee said, at a recent talk in London, she found herself intuitively switching her camera’s focus back and forth between the woman and the forsythia, allowing one to one eclipse the other.

“Milk and Sap,” 2017.

“Dark Matter #1,” 2016.

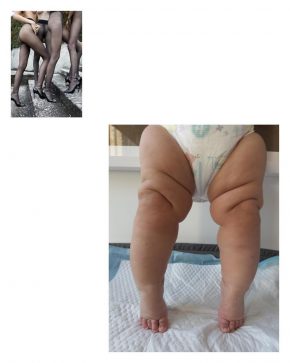

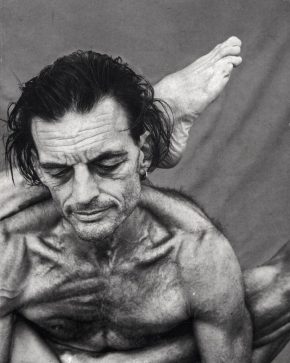

The ongoing project, which is nearly ten years in the making, Lee said, is about “a shift in perspective where a body (portrait) becomes a landscape; a still-life becomes a portrait; and a landscape becomes a body.” A nude lies on moss in the forest, the softness of her body connecting to the uneven texture of the ground and perhaps becoming subsumed by it. The legs and arms of a hidden figure poke out branch-like from around the curved trunk of an apple blossom, as if the unseen girl, like Daphne, is turning into the tree itself.

“Dark Matter #13 (Sinking Rose and Sunflower),” 2017.

“Forsythia,” 2016.

Rather than the exchange between camera and subject, these painterly pictures—currently on view at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art—reveal a symbiosis between human and natural forms, each enhancing the other’s uncanny, shifting beauty. There is a “Winter Venus,” a flame-haired nude wandering among a thicket of branches, and a sunburnt odalisque, her skin as bright pink as the flowers growing from a nearby bush. A young woman, shown spotlit at night, sits on the ground, surrounded by fallen apples, their bruised, pockmarked surfaces echoing the dimples that dapple her exposed skin, the dirt on the bottom of her feet. Another woman, much older, floats naked in a cove, her arms outstretched above her head, her breasts and the tops of her thighs breaking the surface of the water like the seaweeds rising around her.

This state of mingling, as Lee calls it, is as evident when she leaves behind her human subjects to examine the natural world up close. Instead of getting rid of the flowers from her wedding, for instance, Lee began to photograph them as well. Left outdoors in a tub, in a New England October, the flowers would freeze overnight. In the day, thawed and floating and saturated in water, the submerged blooms attained a liquid, filmy cast as they decomposed and became transfigured, as if alive, into startlingly altered form.

“Winter Venus,” 2016.

“Raising the Cherry Tree,” 2016.

“Dark Matter #3, (Wedding Flowers),” 2015.

“Quitsa Pond,” 2016.

“July burn,” 2016.

“Riding the Apple Tree,” 2016.

“Northwest Forest,” 2017.

Comments