Hailing from an era when regular people were street corner legends, Gottfried – who sadly passed away yesterday – is remembered by friends, collaborators and through her archive

American columnist Cindy Adams’ famed bon mot could easily caption any number of photographs in the archive of Arlene Gottfried. Whether partying in legendary 1970s sex club Plato’s Retreat, hanging out at the Nuyorican Poet’s Café with Miguel Piñero, or singing gospel with the Eternal Light Community Singers on the Lower East Side, Arlene was there and has the pictures to prove it.

“Arlene was a real New Yorker who thrived on the energy of the city, roaming the streets and recording everything she felt through a deeply empathetic and loving lens,” Paul Moakley, Deputy Director of Photography at TIME observes.

“Arlene was a real New Yorker who thrived on the energy of the city, roaming the streets and recording everything she felt through a deeply empathetic and loving lens” – Paul Moakley, Deputy Director of Photography at TIME

It was in her beloved city that Arlene Gottfried drew her final breath. She died the morning of August 8, after a long illness that may have taken from her body but never from her heart. In the final years of her life, she experienced a renaissance with the publication of her fifth final book Mommie (powerHouse, 2015), sell-out exhibitions at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, and the 2016 Alice Austen Award for the Advancement of Photography – all of which she attended to with a style all her own.

Long before I met Arlene, I came across a manila folder marked “Mommie” inside a filing cabinet at powerHouse Books back in 2000, right after I started working as Marketing Director at the then two-man publishing house. As I flipped through the pictures Arlene took of her grandmother, mother, and sister I remember my body changed temperature entirely too quickly.

First, a flush of familial warmth as I gazed upon three generations going about their daily lives on New York’s sidewalks; then a devastating chill that ran down my back as I paged through the pictures of Arlene’s mother during her final days in excruciating pain, followed by images of the moment of death. I shut the folder and put it back where I found it, completely unnerved and unable to make sense of what I had just witnessed. I didn’t know you could do this. I didn’t really understand why you would. But 15 years later as I sat in Arlene’s home, interviewing her for Mommie, it all began to make sense.

“What was your grandmother’s name?” I asked.

“Minnie Zimmerman,” Arlene answered, like I might have asked too much.

“Ohh! I love it! Min-nee Zimmah-min!” I said, doing my best Fran Drescher impression.

Arlene let out a full-bellied laugh that I can hear in my mind’s ear as I type these words. She knew I knew things that can’t be said and, in that moment, she began to relax. And that’s when it hit me: I was Arlene, and she was the subject of her photographs, and my job was to channel her so that her words became a picture-perfect portrait of her life.

“Thousands of people have photographed New York but she’s the only one who can take these pictures” – Daniel Cooney, founder of Daniel Cooney Fine Arts

“Thousands of people have photographed New York but she’s the only one who can take these pictures,” observes Daniel Cooney, who showed work from Sometimes Overwhelmingand Bacalaitos & Fireworks (powerHouse books, 2008 and 2011) at his New York gallery. “It’s her – her way of relating to people, her way of seeing what’s around, and her gentleness is what makes it so special. She was very humble and that’s why people let her into their lives.”

And let her in they did, time and again, to the point where you gasp and gape and giggle and choke with tears. I like to say a portrait of the artist is always their subject, and in the work of Arlene Gottfried, this is proven true. Here it is: love and loss, triumph and tragedy, the very essence of human existence that defies time and space.

I operate on instinct; I only think after the fact. So when I reached out to Arlene one day to ask about the one book I didn’t work on – The Eternal Light (Dewi Lewis, 2002) her first – I was unprepared for the truth. I thought we were going to talk gospel as Arlene had invited me to a number of her concerts, where she sang in church, where I saw the Holy Spirit move through her and felt it deep within my bones. I thought we might talk music and the Black Church and the power of spirituals to uplift the soul. But instead, Arlene told me the story of little Monet, a little black girl killed by her mother’s boyfriend and how this tragic death was the catalyst for this series of work.

And then I understood what cannot be said: what has to be sung, cried, howled, and hugged. Why we hit the high notes and the low notes, in joy and pain. Why we take photographs…so we don’t have to explain.

“Arlene was a New York original who had a keen eye, a big heart and a sly sense of humour. I loved her vintage work from the Lower East Side, which portrayed her Puerto Rican neighbours with warmth. She got it because she could relate” – David Gonzalez, co-editor of The New York Times Lens Blog

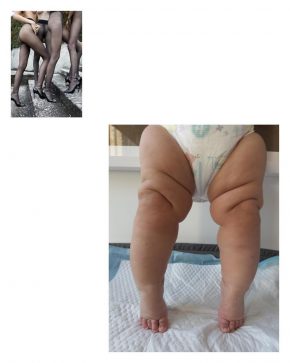

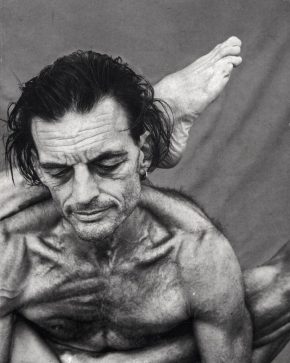

It was this spirit that characterised Midnight (2003), her first book with powerHouse and the first opportunity for me to get to know the woman behind the camera. We watch as a beautiful young man (Midnight) falls victim to mental illness and transforms before our very eyes in a series of photographs Arlene made over a period of 20 years – and against all odds, something in his spirit continues to shine, this profound sense of essential self that transcends the ravages of life. Midnight allowed Arlene to see him at his most vulnerable, at his most playful, his most debonair. You feel a love that goes beyond the flesh (although you feel that too!). In Midnight, Arlene shows us the unbreakable bond between artist and muse.

That bond became forged on the streets of Alphabet City and the Lower East Side where her family lived in the 1970s. As a native New Yorker, Arlene was happiest being a part of the local community, be it Latinx or African-Americans who made up the heart and soul of the city long after it had long been abandoned and left for dead by the government under the ill-fated policy of “benign neglect.”

“Arlene was a New York original who had a keen eye, a big heart and a sly sense of humour. I loved her vintage work from the Lower East Side, which portrayed her Puerto Rican neighbours with warmth. She got it because she could relate,” observes David Gonzalez, co-editor of The New York Times Lens Blog.

Ultimately, Arlene’s inimitable ability to connect to the world in which she lived is what draws us in: each photograph is a gesture of welcome, a friendly hand, a big smile, a hearty laugh, a hand supporting your back, and a tissue to wipe the tears. No matter where she goes, there she is – the ultimate guide to Old York’s most intriguing, most alluring, most exciting personalities. What’s more, there’s nary a celebrity in the bunch, because Arlene hails from an era when regular folks were street corner legends – and that was enough.

“That’s what made us have to publish her. Not her work; her” – Daniel Power, publisher of powerHouse Books

“Looking at Arlene, through the prism of her last book, Mommie – in addition to experiencing her in person, a warm embrace of smiles, giggles, and love – it’s hard to picture a young artist that was to so completely absorb and reflect back the vast arrays of human experience she came upon and made her life’s work,” reflects Daniel Power, publisher of powerHouse Books.

“Arlene allowed us to see, and vicariously experience, the ecstasy in The Eternal Light; the mind-bending portrait-in-time of a Times Square hustler slash fragmented city sprite in Midnight; the beach ball-bounding celebration of classic, old-timey idiosyncratic New Yorkers in the 1970s in Sometimes Overwhelming (note only sometimes!); the biggest heartfelt love letter to that deep nexus of New York flavour in Bacalaitos & Fireworks; and lastly, the moving and unflinchingly honest depiction of three generations of Gottfried women in Mommie. Her core was ebullience, quiet fortitude, acceptance; love. That’s what made her photography so good. That’s what made her singing so amazing. That’s what made us have to publish her. Not her work; her.”

Because, when it comes down to it, there’s really no distinction between Arlene and her work. I discovered this the day she launched Mommie in the ground floor gallery of her longtime home at the Westbeth Artists Community in the West Village. The room was full and Arlene was ready to start, so I thanked everyone for coming, introduced her, and the floor was hers.

With the grace of a woman who has stage fright until she opens her mouth, Arlene took command of the room as she began to read a selection of work from Mommie. The room was entranced as she spoke, giggling at the punch lines, then silent as she described the scenes that they saw in her photos in her own words. And I stood there alone, silently punching the air and nodding to myself: “It works! It works!”

Arlene was reading her own words as though she had never said them before, as though she wasn’t even reading but was finally able to open up in a way she could never do before. Although she could perfectly describe a scene, Arlene preferred to keep her words to herself and let her pictures not just tell you but show you and let you feel it for yourself.

Comments