Panel session (Mar 31 ’18)

Ide:

First, I’d like to thank everyone for gathering here today. The purpose of this exhibition is to showcase the various items introduced throughout Mr. Hiroki Nakamura’s monthly series, “My Archive,” which has been published in POPEYE magazine for over six years, starting in June of 2012, and is set to be published as its own book. This monthly column began when Mr. Kinoshita was appointed as the editor-in-chief of POPEYE, and will end with this year’s May issue, when he will step down from this role. What led to the beginning of this series?

Kinoshita:

I worked in the editorial department of BRUTUS before coming to POPEYE, which is when I first met Mr. Nakamura, and I became curious not only about his brand, visvim, but also about him. So, when I started working at POPEYE, I consulted Mr. Nakamura about working together on a series geared towards our young readers. Of course I was interested in his clothing designs, but I wondered if we could focus instead on his personal stories behind each creation and told him “I wanted to know more about what he was interested in at the moment.” In response, he proposed a rough concept of what he wanted to do, and that marked the beginning of the series.

Nakamura:

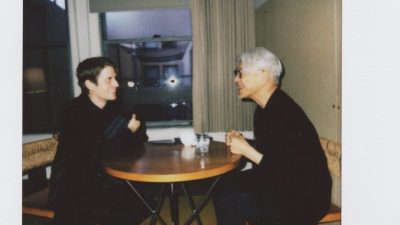

That’s right. We agreed to talk about the things that had given me inspiration during my design process. We got together once every 2-3 months, where I prepared each item individually and we sat down for a chat while looking over them. It was a really enjoyable time for me.

It’s really interesting seeing all of the items on display here today, and it takes me back to all the new things we discovered along the way. I was able to look at things I already knew from a different angle and which provided me with new perspectives. I think that this act of gathering things itself invites that sort of rediscovery.

Kinoshita:

The National Museum of Ethnology located in Osaka houses something similar to these where various handicrafts and folk art pieces from around the world are displayed. It’s a very interesting museum filled with a vast number of exhibited works, but have you ever had the chance to visit it Mr. Nakamura?

Nakamura:

No, I haven’t yet.

Kinoshita:

After about one year had passed since the series started, I became fascinated with Mr. Nakamura’s collection, and realized they were quite a different variety from the items displayed at the National Museum of Ethnology. I think that the items in the museum are all historic, valuable and rare, but to me, Mr. Nakamura’s collection felt much more personal. To me it felt as though the items chosen by Mr. Nakamura expressed what he was interested in at that moment rather than placing the focus on their value in the world. Typically in an “archive exhibition,” one may think that only a limited number of items would be gathered and displayed, but what makes this exhibition unique is that it feels more like a collection of extremely personal items.

Ide:

I agree. Mr. Nakamura’s collection spans a wide range of countries and generations, and many of them cannot be grouped into a category of standard antiques. In fact, many of the items would not be recognized as having significant value as an antique.

Among the exhibited items was a vessel made in the United Kingdom featuring an imitation Imari-style design (porcelain made during the Edo period.) This is essentially a “fake” item, so when looking at it from the perspective of the value of an antique that is recognized as an original item, it is practically valueless.

Nakamura:

Yes, that may be true. It only cost about six pounds, if I remember correctly.

Ide:

I think that is what makes your collection so appealing, the fact that you are not hung up on this existing value system, what kind of things do you look at when selecting your items? Do you have some sort of criteria that you follow?

Nakamura:

I think that anyone experiences a feeling of, “there’s something I like about this,” when looking at something, and there are times when certain items get caught up in your own “filter.” And everyone has their own unique filters that are different from others. This feeling does not necessarily come from the fact that a specific item is collected by many people, or that it is worth a lot of money.

So what triggers that feeling inside myself? Thinking about that can help serve as a hint when creating something new. Some kind of inspiration must have existed when these items were made as well, right? And that’s what I try to imagine on my own. For example, if I see a vessel with a fish pattern on it, I would think, “what kind of fish did the creator look at when drawing this?” By continuing to collect and think about items in this manner, it helps to activate my own filter.

Ide:

There are many handmade items, items that have been naturally dyed or were made using traditional methods in your collection, but not all of them necessarily fit into that same category.

There are many items here that were made with machines, including cars and motorcycles. Does this mean that you weren’t thinking about “only collecting handicrafts” from the start?

Nakamura:

Yes. As a result of going out and discovering things that triggered my own filter, many of the items just happened to be naturally dyed items or handicrafts. In the beginning, I didn’t know about the history behind most of the items as well. As I conducted research while asking myself why I felt attached to specific items, I later discovered that many were naturally dyed. That kind of “information” was typically revealed later on. I’m often asked whether “I make things in order to preserve traditional manufacturing techniques,” or “if I make things using natural methods in order to preserve the environment,” but I never thought of it like that. I just want to make things that will stand the test of time and remain in peoples’ hearts, so first I like to think about what resonates with me, and I use that as inspiration to make new things.

Kinoshita:

Well the people who made the items on display here probably didn’t naturally dye them in order to preserve the environment. However, when I look at these Native American moccasins lined up here, it almost seems strange that the people of that era applied such fine workmanship into their everyday tools. Was the aesthetic conscious of these people from the past that high? Mr. Nakamura, why do you think these kinds of items were made?

Nakamura:

Well, if you continue to delve into it, I think that it comes down to “craving attention.” For example, we made a special space where we exhibited Native American conchos, but these items were originally made by Native Americans to attach to their medicine bags after seeing the rivets attached to the boxes brought in from Europe around the time Europeans and Native Americans started to trade with each other.

I think there was an honest sense of wanting to “dress up” and “wearing different things than others to get the attention of your peers” with an underlying desire “to be loved.”

Ide:

I see. However, I think both people from the past and people today share that feeling of “wanting to be loved.” If that’s the case, why do we feel such beauty in these kinds of old items?

Nakamura:

I think that you can feel that in both items from the past and items from today. However, old items are preserved as archives for long periods of time and have accumulated over the years. There were also a wider number of options compared to modern items. Also, compared to modern items, older items were not made for commercial purposes, so the messages of “wanting others to look at you” or “wanting to be popular” are conveyed in a more direct manner. There were no fashion shows and people telling you what the latest trends were, so it completely removed any artificial biases. I think that the simpler the message is, the clearer and stronger it is.

From a commercial perspective, obviously we run a business by making and selling products, but personally, I initially think solely about what I want to do and what I want to make, and it’s not only about business. I think of it as a process that starts with an inspiration that leads the desire to make something beautiful and long-lasting, and then thinking about how to connect that to a business in order to make that idea a reality. When you reverse this process, and think solely about the business side and then make something that fits those needs, it will change your final product. That’s why I think that it’s important to connect your personal feelings, like making something that you would want to wear or think is beautiful, with the market. Mr. Kinoshita, what are your views on this idea?

Kinoshita:

I absolutely agree with you. I think that it’s especially important to grasp what your objective is in the beginning. I think that for Mr. Nakamura, he has continued to work with the desire to express his tastes to others, and for myself, I had the desire to create a magazine that people would enjoy. Both of our starting points were different from the idea of solely wanting to sell a lot of products and make money.

However, in order to make this happen, you also have to think about how you’re going to make it into a business at the same time. I think that this is important in terms of how things work in today’s world, but I also believe that it’s essential to not forget about initial intentions throughout the process. I love that my own views on this concept relates with the products Mr. Nakamura creates, as well as his own views.

edit&text: Kosuke Ide

Takahiro Kinoshita

Former editor-in-chief of POPEYE magazine. Born in 1968. After serving as an associate editor and fashion chief for BRUTUS, he was appointed as the editor-in-chief of POPEYE in 2012. He stepped down from the position as of March 2018. In May 2018, he was appointed as an executive officer at Fast Retailing Co., Ltd.

Kosuke Ide

Editor. Born in 1975. After serving as an associate editor for travel magazine PAPERSKY, he started conducting freelance work. He currently serves as an editor and writer for “Tsubasa no Oukoku” (Wingspan), the inflight magazine of ANA Group, as well as a collection of mooks, books and online publications. He was in charge of the editing for “My Archive” since its inception.

Comments