A member of New York’s underground performance circuit for over a decade, Narcissister stages visceral and subversive stripteases, challenging ideas concerning femininity, race and glamour—By Kathryn O’Regan

1 April, 2020

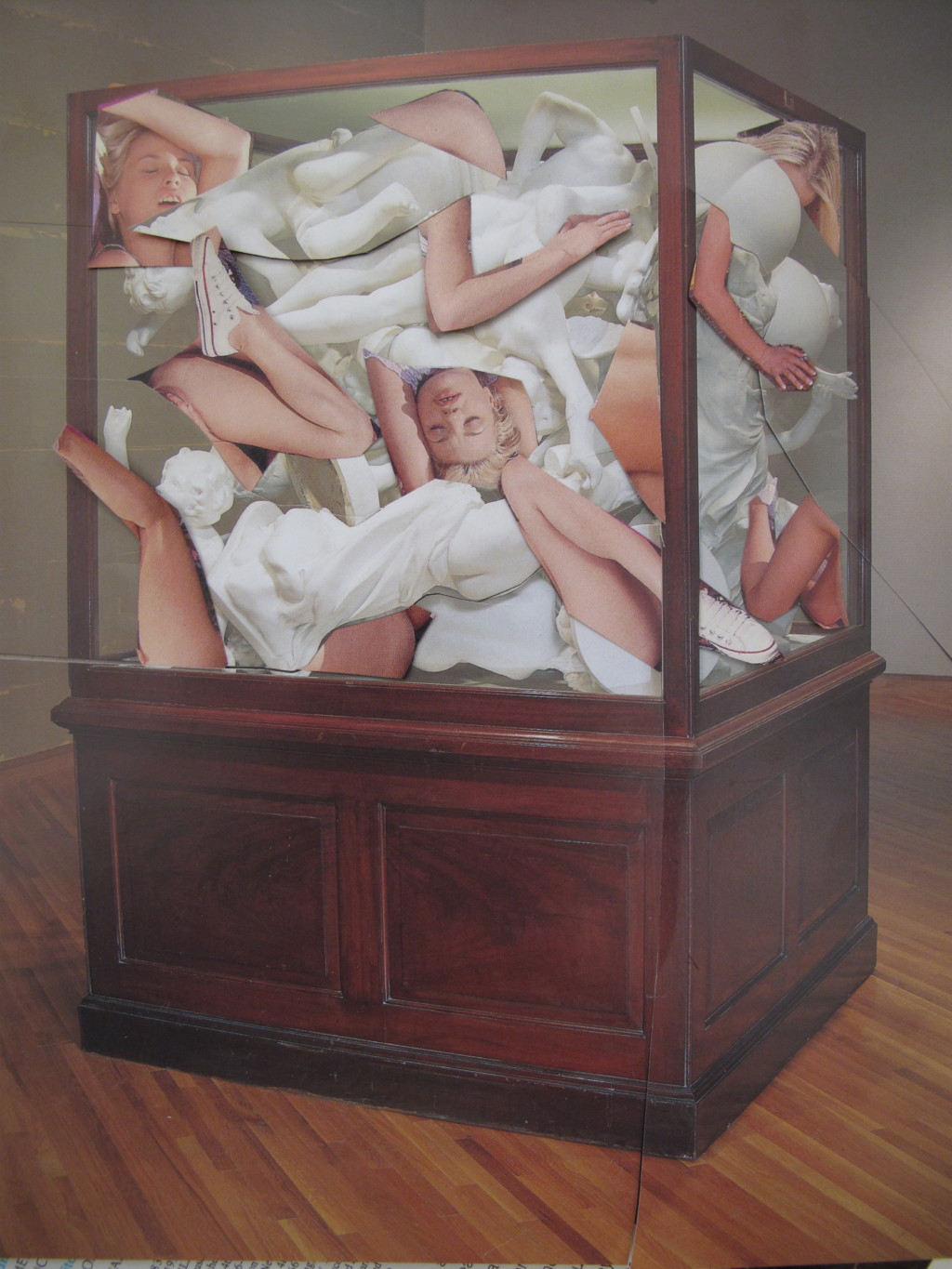

Marilyn, 2016. Video Still.

In 2011, the American performance artist who goes by the name of Narcissister appeared on America’s Got Talent before a judging panel comprised of Piers Morgan, Sharon Osbourne and Canadian comic Howie Mandel. Grainy YouTube footage shows the artist emerging onstage in a fairy princess-type cobalt-coloured cloak to the formidable opening chords of Beethoven’s ‘Fifth Symphony’. She swings and spins around the stage, unclips the cloak, gracefully falls to the floor and pulls her body upwards into a handstand. Beethoven somehow segues into Diana Ross’ disco classic, ‘Upside Down’. Her clothes transform into a frilly tumble of petticoats and bloomers, both sides of her head bizarrely concealed by an eerie Barbie-style mask. As the performance comes to an end, she glances towards the floor, her fringe coquettishly falling into her eyes. And in that instance, doll mask or not, her coy expression looks real.

For a performance artist whose work is built around the premise of wearing this uncanny mask (ordinarily just concealing her eyes, nose and cheekbones), the question of what is real and what is illusory is of major significance. A member of the underground New York performance art circuit since the late Aughts, Narcissister (whose real name is Isabelle, although she prefers to remain anonymous) started to wear the mask in 2007 as a means to create art that could communicate ideas of what it means to be a woman, an artist and a person of colour, without commenting on what she refers to as the “narrow confines” of her own personal experience. Working first as a dancer in New York, she started to support herself with commercial projects, styling window displays. “I realised I could combine my work life with my visual art which was about identity and exploring womanhood and the body and race,” she explains. Meanwhile, the name ‘Narcissister’ (an obvious reference to perhaps contemporary culture’s greatest flaw – narcissism – but also to her being a woman of colour, or a “sister”, as she says) derived from a similar impulse. “I needed to move away from dealing with my own personal experience and my own faith, and so I knew if I picked a different name and wore a mask, I could make statements that were much more broad,” she explains. “For me, wearing a mask makes the work surreal.”

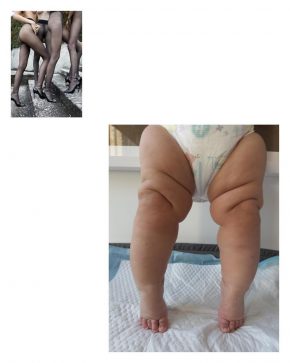

Narcissister. Man Woman, 2007. Photo: Tony Stamolis.

In an epoch defined by the phenomenon of what Jia Tolentino referred to in The New Yorker last December as ‘The Age of Instagram Face’ – the ubiquity of a technologically-engineered (through apps like FaceTune and ultimately, plastic surgery), uniform and cyborgian beauty among women – the idea of a woman wearing a mask as part of her professional artistic persona is not all that different, or even strange, by comparison. One is a mask in a literal form, and the other, just a mask by other means – fillers and injections or gleaming filters, a sheer veil of digitally-rendered, poreless skin.

Narcissister’s shape-shifting performance art orbits around the artifice of identity, particularly femininity. While she assumes a mask to conceal her face, her body is mostly naked apart from the addition of garters, suspenders and a merkin. A number of her performances involve the motion of pulling clothing items and objects from her orifices, and take the form of a visceral re-interpretation of striptease or burlesque. Her work frequently encompasses the tropes and signifiers of a typically feminine form of glamour, one with its roots in old Hollywood: pearl necklaces, fur stoles, long hair, high heels and lingerie. In this case, it is a stirring DIY juxtaposition between socially-prescribed feminine pageantry and a sort of gross-out, carnal spectacle. For her, the erotic aspect of her work allows her and her audiences to “access boldness and personal freedoms in whatever forms that might take”.

One of her signature performances, Marilyn (2016), operates on this strangely abject plane. Wearing an icewhite, peroxide-blonde wig in reference to the Hollywood siren, Narcissister enacts a reverse strip tease by gradually dressing herself through garments pulled out of her vagina. The performance illustrates many of the defining concerns of her practice, of femininity and beauty, glamour and artifice. “One of the first posters I acquired to decorate the walls of my bedroom as a young teenager was of Marilyn Monroe, even though I knew virtually nothing about her or her work. I just found her to be so glamorous,” she remembers. “She was beautiful in ways I certainly was not, but aspired to be. I recall being struck by what my mother told me at the time about the truth of her beauty – how fabricated it was – and also how troubled she had been. None of this was conveyed in the beautiful image of her in the poster! It’s no surprise she came up in my work both as someone to revere and to complicate.”

Studies for Participatory Sculptures, 2015.

The same premise of reverse striptease is seen in the performance I’m Every Woman (2009–), where she dances naked to Chaka Khan’s titular track. Amusingly, the performance cropped up in a 2012 episode of the British sitcom Absolutely Fabulous, with Jennifer Saunders’ hedonistic Edina suggesting that she and her friend – the even more off-the-rails Patsy, played by Joanna Lumley – go and see one of Narcissister’s shows. “She’s a kind of crazy disco performance artist; she pulls things out of her pussy on a rotating platform singing ‘I’m Every Woman’,” explains Edina.

But while Edina’s description emphasises the outlandish humour that is no doubt an element of the performance artist’s work, it’s not the full story. In fact, Narcissister’s practice has emerged out of a rich history of performance art and photography. This heritage arguably begins with figures like French Surrealist Claude Cahun, who Narcissister refers to as a “heroine” of hers, continued in the Sixties and Seventies through the work of radical feminist artists such as the late Carolee Schneemann (who died last year, and whose work was the subject of a panel discussion featuring Narcissister at Art Basel Miami in December). Later, in the Eighties and Nineties, this combination of practices found its highest articulation in the staged photography of Cindy Sherman. Narcissister – who is set to perform at the Centre Pompidou in March, and has a residency at Artport gallery in Tel Aviv in the summer – considers her work to be a “homage” to these artists. “I would like to think that I’m a modern-day version of that kind of work. I’m an heir to that lineage,” she says. Narcissister references Schneemann’s Interior Scroll performance in particular as a longstanding inspiration of hers. The influence is obvious: in the 1975 performance, held as part of the group show Women Here and Now in East Hampton, New York, a naked Schneemann extracted a derogatory review of her work by a male critic from her vagina. Narcissister does, however, acknowledge that historically the feminist art canon was “overwhelmingly white” – “I take on their mantle but make it more relevant for today and also more relevant to me as a woman of colour.”

Narcissister. Man Woman, 2007. Photo: Tony Stamolis.

The daughter of a Sephardic Jewish mother from Morocco and an African-American father, Narcissister – who grew up in La Jolla, California and studied Afro-American studies at Brown University before earning a scholarship to study modern dance at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre in New York – says she has “always been aware of the malleability of gender and race”. In a performance like Upside Down on America’s Got Talent, the metamorphosis of identity is explored through dramatic costume switches and playful theatrics, but this is just one example of a constant desire to investigate the fluidity of identity and the possibilities allowed by that in her work. “To me, there’s something that’s very freeing about not staying fixed in any one identity,” she says. “And I think I understand this very much from my own experience – feeling the complexity of identity within me … I can tear away this identity that I’m embodying in costume-form so quickly, so swiftly and then suddenly I am someone else. I can be a man and I can really feel the power of that, and then I can be a beautiful blonde woman – the kind that I felt oppressed by growing up in Southern California – and I can revel in that, in feeling what it’s like to be this beautiful blonde woman and then I can tear her away. For me, it’s just very liberating.”

The assumption of multiple, changing identities has a long history within feminist art, with artists like Cahun and Sherman probing the artifice of femininity through masquarade. But Narcissister’s work, following this lineage, illuminates how the donning of masks and the appropriating of archetypes is not just a way to emphasise the set of socially-constructed codes and visual spectacles that constitute femininity. On the contrary, it also shows how masquerade can be a source of subversive power for those who identify as female.

In her autobiographical 2018 film, Narcissister: Organ Player, the artist states, “[I could look] at myself more deeply as a character with a mask than I could without it”. For her, the reasons for wearing the mask are twofold. On the one hand, it operates as a mirror: “Whatever the audience’s thoughts or projections are about her [Narcissister] are reflected right back at them. It is a strategic tool,” she says. And on the other, the mask has provided her with a shield with which to protect herself and to create the sort of provocative, charged art she has always wanted to. “I knew from the beginning I wanted to make work that was overtly erotic, and the mask protects me while I am doing that work that would otherwise leave me feeling very vulnerable, afraid or exposed.”

Narcissister: Organ Player, which premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival (this year, the artist presented a short called Breast Work at the event), untangles how her complex family history, and particularly her intense relationship with her mother (whose death in 2012 the film poignantly describes), compelled her to create the character of Narcissister. While she knew that her alter ego allowed her to explore spectacle, humour and eroticism, the artist was surprised to learn what a comfort the character of Narcissister would be through times of grief and loss. “There are no limits to what I can explore as that character … Through her, I can also embody some of life’s heavier themes and moments. That’s what ‘no limits’ means to me in my work.”

At the end of the film, Narcissister swims naked underwater to scatter her mother’s ashes. As the credits roll, Candanian musician and fellow performance artist, Peaches, sings over a glittering electro beat: “I’ve got light in places you didn’t know I could shine” – a poetic reminder of everything that Narcissister is about.

Comments