Previously, your work was photography and collage based, what provoked you to begin constructing sculptures?

The photography was integrated in the collage work—the polaroid depicts a person, and the collage presents the environment surrounding that individual. What I greatly enjoyed was composing and building the image. Eventually, I, too, started to build these environments, rather than drawing them, or building single elements, like different cages for my head, for example. Little by little I had a whole shelf full of objects that functioned as props for these images, so to speak. Then I thought it would be interesting to take pictures of each body part in its perfect position (from a fashion photographer’s eye) and combine these back again into a whole body. It was too flat for me, I got clay and built them as three-dimensional objects. They were rather grotesquely beautiful.

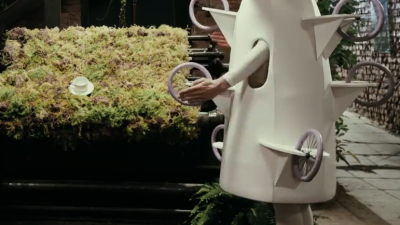

A little later, I started a project of a very different nature, I collected memories from people above the age of 85, I was curious about what it was that they remembered most vividly and whether or not there was a pattern. I created a color-coded chart that resembled a heartbeat print out of a hospital monitor and decided to use fabric—stitching these results onto long strips of fabric. It felt again too flat as a two-dimensional work. So I built a set of small, simple wooden heads and covered them with burlap and started stitching the results onto these little heads. Throughout the last 20 years I have built a good amount of objects or small sculptures, much more than I had previously realized, but a full-focused conversion to sculpture only happened once I started working on a larger performance sculpture, Dystonia (2013), that kept me occupied for 18 months straight. After the performance sculpture, I set out to find a workspace upstate, converted the garage to a studio and started working only on sculpture.

What was the construction process like, considering spatial dimension?

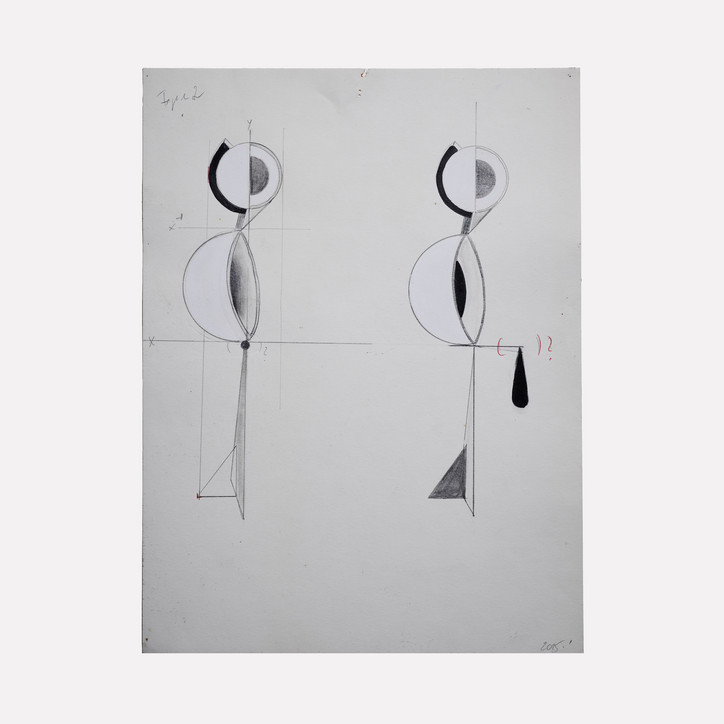

The construction process usually begins with a simple x and y axis drawing and from there on I integrate geometric forms. Its origin is kept in relation to the human body: the 0 point representing the center of an average human body. Once that is in place, I start shifting the forms depending on what I am setting out to build. In Matrose (2018) for example, the extended line representing the neck means a challenged relationship from body to head—the distance is too long, too thin and evokes the sense of a fragility, yet I can counterbalance that fragility with a heavy head, perhaps leaving a negative space that will find its volume again by creating an overly extended base. Its enjoyable to me to find the different ways to balance a challenged character into a solid structure and also to find beauty in the different ways it can function. There is something rational in the balancing act that I find comforting. To recognize and re-organize the spatial dimensions as well as distributing their balances in relation to a human body—even though abstractly—and to remain in the nature of each character is the part I very much enjoy.

Above: ‘A2C4’ and ‘Head 10’

You decided to include your diagram studies, which gives insight into the structural background of the sculptures, Why did you choose to include these depictions?

These drawings represent the issues that need to be contained or re-ordered in the sculptures—the more colorful and all over the place, the more I find them in need of organization and in need of creating their individual forms for their volumes of thoughts and desires. I chose to include them as I think they would be helpful to understand where the forms derive from and ideally why. I have to think of a circus right now—imagine you are in it and then someone puts a huge sheet over the entire circus area and all you see is the surface. It’s somewhat the same thing.

Why did you decide to integrate wood, bronze and brass into your creations?

I didn’t exactly think about it too much as it felt obvious to me, wood was the necessary component as it adapts and reacts to its environment. At one point I needed a more solid material—something that resembles a core and that will not change; I consider it the spine of a character, unbendable and immune to exterior challenges. Bronze seemed to be the obvious choice to me given its nature, and partly its historical use.

Above: ‘1/2’ and ‘4/1’.

Do you consider there to be a balance between geometric form and organic form?

In a purely natural manner—no, unless the geometric form is a sphere and was to be combined with a sphere like organic form and both are competing for balance (my Kugelmann project is about that challenge), there wouldn’t be any reason for it as it’s unlikely to happen naturally. If you mean whether or not it plays a role in this work—yes, and it depends entirely on each work as to how much it had to adapt to remain balanced. Matrose (2018), for example, is much more balanced in geometric and organic form than 2/2 (2018), where the only indicator that it belongs to that group is the base. This body of work remains close to the anthropomorphic nature, but it could potentially go into very extreme shapes and forms.

What does “balance” mean to you?

Equal weight or volume distribution, or the absence of either as long as there are indicators that it is in fact missing.

Above: ‘Head 5’ and ‘Figure 2’.

The finished sculptures suggest similarities to the human figure. Why did you decide to incorporate this particular motif into your work?

Think of children’s drawings for example, most of them have a sphere or ellipsoid as a head, then either a sphere or a cube as a torso, the arms and legs are likely to be a cuboid and hands and feet a mixture of such. Very straightforward and non-descript except their presence—with time they will redefine themselves into more individual forms. The principle is the same in my works—I start out very simply and add and change according to my knowledge of each character, and as they are based on humans their appearance is consequently anthropomorphic. Yet to keep it universal, or non-descript and also not emotionally charged, I will stay in the geometric field as I have no desire to portray physicalities in form of appearance but more of their individual arrangements they chose for themselves—or as I have chosen for them.

Do you always feel drawn to the human form when working on a new piece?

Yes, because that is the only scale and relation I can completely relate to and therefore the only form I can clear-mindedly abstract from (for now).

Above: Collection of miniature models, and ‘Round’.

Do you view your finished sculptures as one entity, or as individual pieces?

The works at the gallery are all individual pieces yet they are all dealing with the same set of issues—their original geometrics or being has been challenged and a modification of form and arrangement needed to happen in order for it to not collapse.

How do you hope your audience will react after viewing your sculptural works?

Hope, for me, always borders dangerously on some form of expectation… I have come to learn that I do much better keeping hopes and wishes quietly to myself.

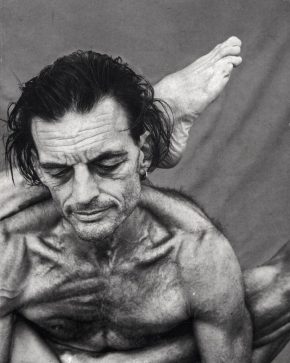

‘Base and Balance; is on view at Helwaser Gallerythrough July 25th, 2019 in New York City. All images courtesy the gallery. Lead image: ‘Matrose’.

Comments