adidas Originals by Hender Scheme | A Conversation with Ryo Kashiwazaki and Erman Aykurt

Interview: Zen Tsujimoto | Photographer: Chad Imes | Translation: Reiko Loucks

Ryo Kashiwazaki | Hender Scheme

September 2nd, 2017 marks a day in the history of adidas which has not yet been seen before. For the first time, the German sportswear company will release a series of footwear in collaboration with another footwear entity, Tokyo label Hender Scheme.

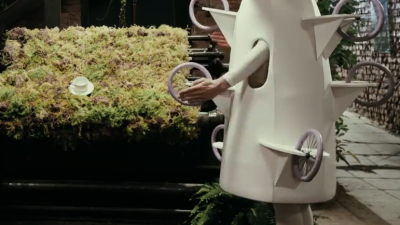

At first glance, the collaboration appears to be a mere update of premium materials and handiwork across a series of adidas silhouettes; taking a closer look however, the cultural relevance of this project is truly astonishing. The collaboration signifies that adidas not only acknowledges the values instilled in Hender Scheme’s Manual Industrial Products, [a line within Hender Scheme that pays homage to iconic sneaker silhouettes], but also celebrates the philosophy of bridging together a ubiquitous commodity with traditional methods of artisanal Japanese craftsmanship, resulting in an entirely new entity. The juxtaposition further finds form through strenuous and highly skilled methods of hand production, meaning that production is restricted to very low quantities. As such, the generation of sales revenue is not the primary motive, placing an art-like value on the collaboration – a radical move in today’s age of accessibility. The range is a timely balance of the authentic and contemporary models Superstar, MicroPacer and NMD, and is entirely handcrafted in Asakusa — a district in Tokyo associated with a rich history of leather tanneries from the Edo period [the close proximity to rivers being a necessity for tanneries for treating leathers].

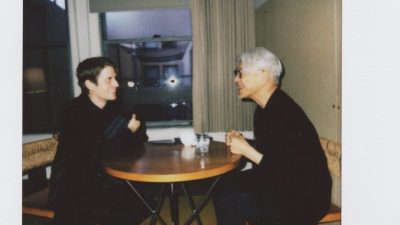

We discussed the collection and its value at length with both Senior Design Director of adidas Originals Statement Erman Aykurt and founder and head designer of Hender Scheme Ryo Kashiwazaki. In our interview with Aykurt, we discover how traditional methods of craftsmanship commemorate the very origins of adidas, when founder Adi Dassler began handcrafting and experimenting with his own creations that gave way to adidas as we know it today. Aykurt further elucidates adidas’ core values as a global brand in today’s society and their reasons for expressing themselves with this collaboration.

We spent a day with Kashiwazaki, where we were given tour of his factories, the Hender Scheme atelier and the recently opened Sukima shop in Ebisu, eventually making our way to the adidas Japan headquarters. Throughout the course of the day, we were given insight into Kashiwazaki’s thought process behind this project. In his ever-calm disposition, Kashiwazaki goes on to philosophize how a product only reaches completion once the wearers have put their own mark on it through daily wear and tear. Read on as the interviews reveal the events that gave way to this groundbreaking collaboration and how this alliance between adidas and Hender Scheme speaks of our times.

“From the beginning, we wanted to bring out the best from both parties, and do something we weren’t able to do on our own individual accords.”

What is your earliest memory of adidas, the one that’s left you with the most lasting impression?

I guess I already knew adidas even before I realised it. I used to play soccer, so I came to know adidas through my soccer boots and sportswear. The brand has always been close to me since I was a kid.

Do you remember which particular models you wore back then?

I think the Predator came out when I was in elementary school. Through middle school and high school, I saw the Predator constantly updated with new technology in each new iteration. On the other hand, there are classics like the Copa Mundial that have remained unchanged. To me, adidas is a brand that is both innovative and classic.

What were the circumstances that led to the fruition of this project?

Friends from adidas Japan would frequent our exhibitions in Tokyo, and some of them would wear our shoes and accessories. Naturally, we have respect for adidas, and they too seem to respect our work. We started talking about whether there was any positive points we could bring to one another, and the opportunity arose from figuring out a way to create a new project or product.

How did you feel when you started this project?

I know our scale is much smaller than adidas, but we wanted it to be a project that was fair to both sides. From the beginning, we wanted to bring out the best from both parties and do something we weren’t able to do on our own individual accords.

With adidas’ global reach and appeal, how do you feel Hender Scheme’s core fans and enthusiasts will be affected after a project of this magnitude?

While I consider working with them to be a milestone for us, our stance hasn’t necessarily changed from working with adidas. We merely continue to do what we originally do. Our derivative tribute works through MIP [Manual Industrial Products] were meant as an homage. To be officially approved by adidas is a symbolic and progressive occurrence for us; I think it is very modern.

“Our derivative tribute works through MIP [Manual Industrial Products] were meant as an homage. To be officially adidas approved is a symbolic and progressive occurrence for us, I think it is very modern.”

Moving forward, how do you think this project will affect Hender Scheme as a brand?

It’s really hard to say until after the launch. adidas is such a huge corporation, so I think it will probably be an opportunity for people who don’t know about us to find out about Hender Scheme. That being said, our stance towards our work will likely remain the same. Our creations and craftsmanship will continue on for a long time.

What kind of experiences can you take away from working with a monumental brand like adidas?

A large component of our process requires a lot of handmade, analogue work. Conversely, adidas is a technologically more advanced company, so their factories are much more advanced as well. Where we can only manufacture 100 pairs of shoes, the scope of adidas allows them to produce tens or hundreds of thousands more, but I think there are benefits in both executions. adidas has a lot more knowledge when it comes to manufacturing and technology than we do; the sheer knowledge was very inspiring.

How would you describe your experiences at the adidas headquarters in Germany?

My most memorable experience was visiting the archive. I was amazed by the fact that adidas could have such a rich history, yet also be a corporate enterprise at the same time. Their archival works are all beautifully stored and organised. Designers are able to go back and reference details of past products to recreate or update designs as modern adaptations. We are only in our eighth year since the brand started in 2010, and while we do sometimes go back and reference our past archives, we don’t have anywhere near the historical depth as adidas. I think there are very few brands where designers can actually go back to their archives for inspiration, so I was really impressed by that.

Can you provide some insight on the working process with the adidas team?

We have mutual respect for each other, so communication was very smooth. Since production was handled on our side for the most part, we were able to execute good control over the finished product and it wasn’t too different for us altogether. If the manufacturing was completely handled by adidas, I think it would have been a different story with different regulations. We had a brainstorm session with the designers where I realized that, although adidas operates on a vastly larger scale with technological advancements unknown to us, there were many fundamental aspects in thought process we had in common, so that was very interesting.

As a global project, you mentioned most of the production was handled in Tokyo. Were there any challenges faced with meeting production requirements when operating with a company like adidas?

Yes, it was quite a strict process that took a long

time, so our production control team worked very hard to meet these requirements.

The adidas team also came from Germany to oversee the production?

Yes, we had to resubmit the leather test as well. There were quite a lot of adjustments.

The collaboration consists of Superstar, Micro Pacer, and NMD, which is an interesting balance of old and new. How were these styles selected?

We had been developing iterations of the Superstar and MicroPacer as part of our Manual Industrial Products (MIP) collection. For the collaboration, we made various adjustments and updates to the shoe lasts and patterns and were finally able to add the logo and the three stripes. We used the unofficial derivative works we had been making in the past, but this time it was finally official via adidas. adidas wanted to bring things one-step further with the inclusion of the NMD, so I made a sample and brought it to Germany for proposal.

The addition of the NMD speaks to current times. What were your thoughts behind the selection of this model?

The basic concept behind our MIP [Manual Industrial Products] collection is to highlight the contrast between industrial products and handmade products. For the concept to carry through, it was important to work with a shoe that is widely known. The NMD is quite a popular shoe with technologically advanced details, so reproducing this contemporary shoe with our analogue and labour intensive methods of production would bring an interesting contrast. It certainly was a challenge, but we picked up the details and recreated them through our own methods of craftsmanship.

We see a lot of people wearing the NMD nowadays, but perhaps this collaboration will bring a new perspective to the style. You mentioned working with the adidas team in Germany, could you explain more in detail the process of working with them?

Until now adidas has mostly collaborated with apparel designers, but this was actually the first time they had partnered with another footwear brand. Hender Scheme falls largely within the area of footwear and accessories, and since we have a reasonable amount of knowledge when it comes to making products, we did the sketching, prototype production, and brought the finished samples to meetings instead of enlisting an adidas designer to carry this out, as may be the case for other collaborations.

“It was encouraging to see that the creative process of a big corporation like adidas was not too different from the process of a small local company like us. It reassured me that, although we are small, what we do is nonetheless important.”

It was the first time that adidas collaborated with another footwear brand?

That’s what had been said. For us, it was much easier to bring the actual prototype in, rather than trying to explain the ideas and asking someone to realize them. We had another meeting in Paris, and I presented my sketches along with the rough physical prototype made by our craftsmen.

“It was encouraging to see that the creative process of a big corporation like adidas was not too different from the process of a small local company like us. It reassured me that, although we are small, what we do is nonetheless important.”

What was the biggest challenge in this project?

I think the most significant part of this collaboration is the fact that the adidas logo will appear on the shoes. The course of events that led our derivative products to be made into an adidas-approved official product is very much a state-of-the-art situation, and I’m really proud of it. It’s not simply about creating a well-designed product, but it’s the implication behind it that makes this collaboration significant. I think that was the most challenging part, and I’m sure a lot of difficult decisions had to be made within adidas to achieve this, given the size of the company. However, I do believe the design methods of anything are based on some sort of precedent, and culture is created by these repeated design updates. Of course I think malicious copies should be eliminated, but if we eliminate too much, we stop the progression of culture, which stops us all from moving forward. adidas uses open source as a key word, which is a movement that we are also very much into. In the middle of this movement, I think it’s groundbreaking that these homage products or derivative tribute creations are becoming an adidas-official product.

As an adidas fan since childhood, did this project change the way you think about adidas?

Absolutely. I saw adidas in a new light due to the sheer history behind the brand, and even though they have many team members involved in each project, everyone is in a great mindset. My respect for adidas grew even more than before. It was encouraging to see that the creative process of a big corporation like adidas was not too different from the process of a small local company like us. It reassured me that, although we are small, what we do is nonetheless important.

What kind of person do you envision enjoying this collaboration?

It’s quite difficult to say, since it’s quite a complicated product. It appears to be a sneaker, but it has leather soles. The leather is delicate, and it’s also delicate to wear. A person is definitely entitled to make the choice if they want to collect the shoes for display, but in reality, I would like people to wear and walk in the shoes. Our philosophy is that we don’t create a 100% finished product, but rather we ask the consumer to complete the product by breaking it in to make it their very own 100%.

What is the most important message from you regarding this collaboration?

The direction of this project meant that our craftsmen would undertake handcraft methods of production, but on the other hand, we were able to showcase the differences in scale between adidas and ourselves. There are qualities on both sides; we both have a place in this world, and consumers are able to choose what products they use in their lives. I hope to be able to send out the message that both industrial and handcrafted works have their perks through this collaboration. The price point is high — there’s been a lot of effort invested through handcraft, and we use very good leather — but that’s not the point. I don’t think that it becomes a good product just because you use nice materials and spent a lot of time on it. The ideology behind this is that this is one of many options, and anyone can choose what they think is great.

Erman Aykurt |

Senior Design Director, adidas Originals Statement

How did you start your career at adidas?

I was working at some design consultancies in Germany and Italy and I specialized in graphic design on industrial products. There were some mutual colleagues at my design consultancy that had connections to adidas and they recommended my services. That’s how it all started a long time ago [laughs].

I’m curious as to what your preconceptions of Hender Scheme were before working with them. When did you first hear about them? What was your initial reaction on a brand level?

I first heard about them quite some time ago. Of course, the first thing that comes to mind is the artisanal approach, but also the fact that he only used iconic sneaker silhouettes, that are mass produced objects that people really care about. It’s a very emotional product. He gave these designs additional love by reproducing them through the artisanal angle and lens. Sneakers have relatively low material, yet very high cultural, value. Ryo-san is almost inversing it. He’s taking the existing cultural value, but adding even more actual material and craft value into the product.

It’s very impressive that you acknowledge the philosophical value straight off the bat. I’m surprised there was no animosity, but conversely that you saw the cultural relevance of what he was doing.

Normally a designer is not involved in any legal claims or activities. I don’t know if you know Masatoshi Kase [Senior Manager of adidas Originals Global activations] — he had a good connection to Ryo-san, so we always knew about Ryo-san’s intentions. There were also football activities and so forth, and some people at Hender Scheme were there too. These were all the touch points with adidas as a brand.

Do these local creation centers adidas has, provide a buffer between Germany and Japan to communicate the significance of what these local Japanese brands are doing?

I wouldn’t say a buffer, but more so to encourage these personal relationships. It’s easy to dismiss something from a lawyer’s desk, but you can identify mutual respect as soon as personal relationships are involved. We always think that’s a good foundation for real collaboration and for bringing the two brands together.

What are your thoughts on the balance of the selection of models on a product level? Can you elaborate on the contrast between the authentic Superstar, to more contemporary models like the Micropacer and NMD?

Ryo-san was already working with the Micropacer and the Superstar with his homage product line. The addition of the NMD then created a good picture of shoes that represented the technological advances through the decades in both lifestyle and actual sports function. I think it’s a good overview of our milestones, and each one had a specific challenge to Ryo-san on how to translate that into an artisanal product. It was selected together with him and he immediately talked about how interesting it would be too. The quite recent sock-like construction presented a very interesting challenge to Ryo-san.

Most companies of adidas’ size would litigate, but you chose to collaborate instead. Can you please explain a little bit of the thought process in that?

I think when intellectual property is misused, it’s usually done to create counterfeit product that devalues the original. What Ryo-san does elevates the intellectual property. I always viewed his homage line as more of a hall of fame, so it was more of a positive reaction to our intellectual property. Of course, this is a good first impression. Knowing that Ryo-san is a big proponent of the adidas brand and wanting to find out more, there was a natural willingness to talk and get to know each other.

What kind of significance does this project hold considering adidas’ history, and how do you think it will impact the industry and market going forward?

“For Ryo-san, I think there is a bigger exposure for what he is doing with adidas, which is not always the aim for collaborations.”

Currently we are tying most of our storytelling around the past and the future, and our creative director Nick Galloway has recently introduced more of a creative culture approach to product design, where designers spend less time in front of the computer and more time actually making something. So of course, working with Ryo-san was a good way to inspire the designers to do more and show them how far you can take it. At the same time, there is also a deeper connection with Ryo-san’s approach to appreciating the life the product takes once it’s with the consumer. That connects with Adi Dassler himself. When we took Ryo-san through the archive in Germany, the archivist explained that most of the shoes were worn samples Dassler collected from athletes to learn about — and also to improve — how a product was worn, used, and how to read the traces of the use. Also, if we look at how Dassler started, it was a similar cobbler approach to athletic footwear. We found old football boots from the 50’s where even the studs were made from leather. That was really interesting for Ryo-san because it’s somehow closing the loop for him. It’s really important to see modern day examples of that, and if we think about how hyped up the market is at the moment, it’s quite imaginable that the market will shift in to more considered or more actual value propositions.

What kind of consumer do you think this project speaks to the most?

People in general care about sneakers, but to care about and spend this much money for a sneaker, people have to care a lot. Fortunately, Ryo-san has this loyal consumer base that is willing to invest in the lifecycle of a product like that. So far we have introduced the shoes at Paris Fashion Week and the response has been very positive. For Ryo-san, I think there is a bigger exposure for what he is doing with adidas, which is not always the aim for collaborations. Ryo-san is someone who wants to grow very organically, so it doesn’t really help if everyone wants Hender Scheme. He will not ramp up his production all of a sudden. At the same time, exposure to his thinking and what he does is something that he will appreciate a lot.

Coming from your humble standpoint, what can a big company like adidas learn from a smaller brand like Hender Scheme?

As I said, the artisanal part of what he does: talking a lot about which leathers to use, in which areas. These were all things that a company like adidas were very good at, but some of those things are rationalized away with industrial manufacturing. At the same time, seeing your own product and your own icons through the eyes of someone who has a deep respect for what you do is always charming. It gives you an idea of what really resonates with the outside world.

It also plays on a reaffirmation point. When you talk about Adi Dassler, the care and attention and the artisanal side, this project brings to light the history of adidas and things coming back full circle. On that note, do you think there are any similarities between Japanese and German craftsmanship in terms of approach and product design?

I think the willingness to learn everyday, to not take every aspect of your work for granted and to see everything as an opportunity for improvement are the similarities in the approach between Japanese and German craftsmanship. I will say that in Japan, there is not only the willingness, but they actually improve every day. That is something that I don’t see as often in Germany.

What are your own personal design influences?

My background is in industrial design, and for that I had to leave my hometown, where I was playing in a few not-so-famous bands [laughs]. I got into design through flyers, poster and album cover design early on. Also, song lyrics got me thinking about how a line in a song can touch so many people. It’s interesting what commonalities and problems youth culture has and how they respond to artistic expression in popular music, which got me interested in being creative with people’s emotional reactions to products. I went to universities in different cities in Italy and Germany, so I came to know about urban life and the culture that comes with it. I am also interested in art and other expressions. Pretty much the biggest motivation for me is pop culture, how it keeps interest up and its evolution. Just seeing how a simple product, like a sneaker, resonates with youth culture and helps them express themselves, their worries and problems and how they need to improve themselves in society and so forth — that’s very interesting to me.

The inspiration is on a much deeper level, an emotional level.

I wouldn’t even call myself a good designer because the actual design I do is relatively basic, but the emotional triggers are something I like to work with.

I can imagine it’s much more subliminal than people think, where the design actually speaks volumes to future generations. What was the name of your hometown?

Ingolstadt. It’s a small city of 100,000 and home to the big Audi power plant.

Was it only once you left for university that you were opened up to different subcultures?

Subcultures, sneaker culture, and playing basketball in university got me interested in athletic products — how people talk about and react to them, how people use them as signifiers for expressing belonging, the cultural attachments and all the notions a sneaker design carries.

You originally worked with adidas Japan in the past. What led to this chapter in your career at adidas?

“It’s not important how many products are being created or how much money we generate, but to use this opportunity to put our character on display and to show the world that we share mutual respect, and then work with that to create good product stories.”

My marketing counterpart and I went there to open a satellite product creation office right in Aoyama. We stayed there for three years and I left Tokyo before the earthquake.

So is the satellite office still here?

No, it’s now integrated into the new HQ. But being in Aoyama was a big influence on me because we were working from a headquarters downtown for the first time, where people would stop by to chat and look at new stuff. It felt much more integrated in a city’s culture, instead of being on a city’s outskirts.

Yes, it makes a lot of sense and it’s very strategic placement. What drew you to Aoyama and Japan, and how does it tie in?

It was more about being close to Harajuku. Aoyama is a little bit too much fashion for myself, but being close to all the tenjikai’s [exhibitions], being able to get out over lunch to say hi to people and to host people was great.

It sounds like you have a great sense of the movement out here that led up to this point. How do you hope this kind of project — limited in quantity and attached with a high price point — impacts people on a macro level?

All of our collaborations display what we are into ourselves and where we see the touchpoints between our brand and other brands. It’s not important how many products are being created or how much money we generate, but to use this opportunity to put our character on display and to show the world that we share mutual respect, and then work with that to create good product stories. I think that is what the consumer is ultimately interested in. In the case of Hender Scheme, I think it is a strong message towards craftsmanship and we would like the world to know that we are into that.

Comments