Multi-talented and multi-genred, Ethan Hawke has always slipped freely between the roles of arthouse luminary and A-list favourite. PORT meets an actor firing on all canons as he relishes a new, more distinguished, chapter in his life

Wool suit DIOR HOMME

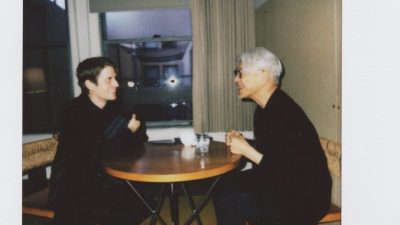

When I walk into a coffee shop in Brooklyn to meet Ethan Hawke, he is already engaged in exactly the kind of conversation you might dream Ethan Hawke has in Brooklyn coffee shops, if you were to dream about such things. A strapping young man in a baseball cap with the galumphing demeanour of a golden retriever has stopped by Hawke’s tiny table to introduce himself. He says he is an aspiring actor (of course) who really admires Hawke’s work and has a few questions about how to stay the course despite the crushing rejections and heartbreaking uncertainties of a life in the arts.

Hawke, who at 45 has only just started to grey around the temples enough to hint at wisdom, kindly shakes hands with the plucky hopeful, flashes that famed Hawkean smile (weaponised dimples; snaggletooth proud), and says, with gravel in his throat, that the only way forward is to focus on finding good material. If the work is worthwhile, Hawke continues, the rewards will come. He wishes the young man luck, tells him he’s been exactly where he is, and that if this is what he is meant to do then he must stick it out. It is the kind of boilerplate hang-in-there-baby message that sounds oddly profound coming out of certain mouths, and, in Hawke’s voice, the message to carry on feels urgent. When Hawke tells someone to keep acting, it feels intense and insistent, like he is a member of a dying civilisation straining to keep an oral tradition alive. Hawke himself lives to act; truly believes in its world-shifting potential and still refers to it as an art form even after three decades in the business. When a guy like that tells you to go for it, it resonates. The young man beams, takes a deep breath, and strides out of the coffee shop into the summer heat holding his drink like a trophy.

Wool suit and cotton T-shirt DIOR HOMME

Hawke doesn’t mind playing the role of old-timer every now and then. In fact, he tells me after the young man leaves, he is thrilled about his age, because it means he finally gets to star in westerns. A boy from Austin, Texas at heart, he tells me he has been waiting his whole life to reach the point where his face matches the genre. “I just finally have enough lines in my face to get cast,” he says. Hawke is wearing a battered trilby and a rumpled short-sleeve button-down, the standard uniform of cool dads haunting Boerum Hill coffee shops during the school day. (His two youngest children, daughters Clementine, 8, and Indiana, 5, are in fact in school just down the street; he walks them there every morning.) “There’s no real place for the male ingénue in a western,” he continues. “Well, sometimes there is, but those aren’t the parts you want to play anyway. They all get killed early or hung by their thumbs.”

This year, Hawke went all-in on the mythology of the American West. He appears in two westerns: one big-budget (Antoine Fuqua’s The Magnificent Seven reboot, out in September) and one indie (Ti West’s grifter drama In a Valley of Violence, coming in October), and he also published Indeh: A Story of the Apache Wars, a graphic novel about the trials of Geronimo in the 1870s told from an Apache perspective. He says he didn’t intend to have all these projects hit at once, but he also sees a kind of poetry in the symmetry. “There is definitely a theme to this year,” he says. “I have been working on the graphic novel for six years, so that’s kind of a coincidence. I definitely work in obsessive cycles. When I was doing the Chet Baker movie, I just killed myself on Chet Baker. There was no rhyme or reason to anything in my day but reading about jazz and trying to practice the trumpet. When I was making a documentary last year, I was hypnotised by other documentarians. That’s just the way I am.”

Micro check wool oversized shirt and wool serge narrow trousers DIOR HOMME,Trucker hat and paatent leather loafers throughout stylist’s own

We start talking about why he is obsessed with the West, why it felt like a subject he needed to tackle right now. “As far as Mag Seven goes,” he says, leaning in, “I would have done that film for free. Don’t tell MGM. But getting to ride horses in the desert with Denzel Washington? That’s fun. With In a Valley of Violence, it’s the total opposite, this low-budget spaghetti western that we made in the middle of the desert outside of Albuquerque.”

And Geronimo? “It’s a mysterious thing of what brings a white guy to want to write about the Apache,” he says, with a slight bow of the head. “I can promise you it’s not that I have any interest in appropriating a culture that’s not mine. But I grew up camping around that territory with my dad, and Geronimo became one of my passions. Then I remember seeing the biopic ‘starring Robert Duvall and Gene Hackman and Jason Patric and Matt Damon and also Wes Studi.’ I remember it really upset me, because I thought: God. What if they made Malcolm X and it ‘starred Jason Patric, Robert Duvall, Gene Hackman, Matt Damon and also Denzel Washington?’ You would never do that. There’s so much white guilt around this story, and yet it is such a good story. If Shakespeare were writing now, he would write about Geronimo.”

Talking to Hawke can feel a bit like talking to the most excited person in a college literature seminar: he quotes Shakespeare; he brings up white privilege and the perils of climate change (“People are going to look back on photos of our traffic jams and think, ‘What were they thinking? Didn’t they know?’”); he waxes misty about the time he interviewed Kris Kristofferson and how it gave him respect for the journalistic endeavour. He is ebulliently chatty, like a pile of words are always at the back of his teeth. And yet, all of these disparate verbal threads somehow coalesce into an artistic fervour that is inspiring rather than exhausting; Hawke always wants to be thinking about something new, creating something new, noodling on a project and a big idea. It seems to keep him youthful, no matter how many weathered lines appear on his cheeks. He seems less like an established actor (which he is; he has two Oscar nominations to prove it) and more like a ceaseless seeker who must keep sparking mental flint to survive. Acting is one way of letting off creative steam, but Hawke says he has never felt satisfied just being in front of the camera.

He has published two novels (The Hottest State in 1998, which he then made into a film and Ash Wednesday in 2002), one children’s book (2015’s Rules for a Knight), the new graphic novel and co-founded the New York Public Library’s Young Lion award. He works as often in the theatre as he does on the screen, having made his Broadway debut at only 22 in a revival of The Seagull, which led to founding the cult-popular Malaparte theatre company with three friends, which lasted until 2000. He has directed three films, including 2001’s Chelsea Walls – a tepidly reviewed drama about five bohemians living in the Chelsea Hotel – and 2014’s Seymour: An Introduction, a documentary about beloved Manhattan piano teacher Seymour Bernstein. He has plans to direct a feature next, an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Camino Real (Williams is Hawke’s great-granduncle), which he hopes to start filming next year in Cuba. “I want to go over there. It’s like the sunset of the 20th century. It’s all right there. You see the Karl Marx theatre, and then Coca-Cola trucks going by. It’s a fascinating moment. I’ve had the rights to the play for five years, but I’ve been wanting to do this for 15 years.”

Hawke wants to remain diversified, free to pursue any artistic whim that zooms into his brain. He realises that being in a position to even think this way is a rare privilege. “I’ve never worked as hard as my father,” he admits, referring to his father James, an insurance actuary in Texas who separated from his mother Leslie when Hawke was four years old. “He got two weeks off a year his whole life. I’ve got months off a year. I get to go on vacation with my kids. I travel. I pursue interesting avenues.”

Check cotton flannel shirt ,cotton T-shirt and wool serge narrow trousers DIOR HOMME

It might be fair to say that without Hawke, more exploratory (or dilettantish, depending on your view) young actors like James Franco and Shia LaBeouf wouldn’t have a model to follow, though Hawke is quick to note that he took his cues for his peregrinations from Dennis Hopper.

“There’s a quote by Hopper in which he says that when he was growing up, he didn’t know you were supposed to pick an artistic medium,” Hawke tells me, flashing that smile again. “He just thought it was the arts, and you were either in the arts or you weren’t. Then if you’re in the arts, you can be like, ‘I love dancers. I love musicians. I love painters and sculptors and actors and songwriters. I just love all that shit. So I pick that.’ That’s kind of where I always saw myself. I didn’t know that there were all these distinctions. I kind of just saw it as dedicating my life to the arts.”

When Hawke talks about being dedicated to his work, it is more than just an abstract idea. If there is any one aspect to his career that has made it stand out from those of other actors that burst on to the scene as bright young things (in Hawke’s case, it happened twice; first with his poignant ‘O Captain! My Captain!’ moment in Dead Poets Society, and then as the grungy romantic heartthrob of Gen Xers everywhere in Reality Bites), it is that he has consistently chosen projects that require a deep and long-term investment, often without any sign of pay-off or even completion. He grinds away on things he believes in, often for decades. He worked on Indeh with graphic artist Greg Ruth for six years, at first trying to get it made as a film, but finding that no studio wanted to take it on.

“When I was first trying to pitch this movie, they just saw it all as so educational,” he laments. “I felt like, ‘You guys! This is going to be the greatest western ever told. It’s going to be amazing.’ But I actually think the graphic novel shows you what a great story it is and makes it come alive in a way that a script was never able to. For example, in the opening of the book, Geronimo’s family gets killed and he’s visited by a hawk. In a movie, does the bird speak Apache? If it speaks Apache, is it translated? If it speaks Apache, is it a female voice? Is it a male voice? All of a sudden, it could be bad, like, comically. But in the book, it’s just a fucking drawing of a big hawk’s eye. You can be graphic about it and pay homage to what really happened, but at the same time it’s clearly art. I found this is the right medium for this story, after all this time.”

Hawke worked on the graphic novel only half as long as he worked on Boyhood, the innovative 2014 family saga that director Richard Linklater filmed over the course of 12 years. Hawke earned an Oscar nod for playing Mason Evans Sr, a somewhat absentee musician father to two children who transitions from cool rebel, to destructive has-been, to a resigned and pensive middle-aged guy playing rock songs in a bar over the course of the long production. Hawke took on Boyhood as a labour of love, admitting that at times he doubted the film would ever see the light of day.

“I didn’t think it was ever going to come out,” he says with a little laugh. “But I did it because I feel like the pursuit of making meaningful, substantive art means more to me now than it did when I was 19 or something. As you get older, you are faced with the inevitable disappointments about how hard the world is, and that kind of crushing pull towards mediocrity. But I’ve seen things penetrate. I’ve been a part of things that have broken through, and it’s beautiful. You kind of chase it. You just keep chasing that brass ring.”

Cashmere double-breasted overcoat with techno membrane and wool serge narrow trousers DIOR HOMME

Another one of Hawke’s multi-decade projects that broke through in a big way is the Before series, also with Linklater, that follows a pair of lovers (Hawke and Julie Delpy) from their swooning 20s to disgruntled 40s over the course of three dialogue-saturated films. Jesse and Celine are always talking, from the moment they disembark a train together in Vienna in Before Sunrise, to their charged reunion in Paris in Before Sunset, to their fraught marital struggles in Greece in Before Midnight. The trilogy is a meditation on time: the way it changes the way two people talk, touch each other, fight with one another. Throughout the three films, viewers get a chance to watch Hawke grow up, but also not as quickly as perhaps they might hope. There is an evolution, but it is subtle, frustrating and often unremarkable. The pair’s maturity is hard-earned, but they still make plenty of mistakes.

Hawke says that in his own life, he has reached a point where he finally feels like an adult, able to own his past errors and see himself clearly. He credits his second wife, Ryan Shawhughes, whom he married in 2008, with surrounding his life with a calm aura. “To be totally frank with you, and it’s something that’s really annoying here,” he says, “but in recent years, my friendship with my wife has been a really powerful force in my life. Because, knock on wood, my life feels on stable ground.”

Though he doesn’t say so outright, his emphasis on marital stability seems to contain a subtle spark of defiance in it, a wink at the fact that his second marriage has settled into quotidian bliss despite the fact that the tabloids once tried to explode it. It is true: Shawhughes did work as nanny for his two children with Uma Thurman when the two actors were still married. But, as Hawke once assured The Guardian, Shawhughes’ childcare tenure was only a brief stop on her way to graduate school, and the two only crossed paths again a year after he separated from Thurman in 2003. “I know people imagine some kind of Sound of Music type love affair,” he told the paper in 2009. “But the truth is by the time Ryan and I were falling in love, it had been a long while since I had employed her.”

Hawke remarked that at the time the divorce from Thurman devastated him, and was one of the reasons he started spending more time out West, camping and staring at the stars to try to relieve the pain. It was then that he got the idea for Indeh and started on the trajectory that has led him to this year. Now, he has an active and healthy relationship with his two oldest children, Levon, 14, and 18-year-old Maya, who will start at the dance and drama school, Juilliard, in the fall.

daughter pursuing the same career path. He laughs. “I remember hearing Paul Newman or Warren Beatty talk about how my generation was worse than theirs. I guess everybody always says that. But I do feel that there’s the pull, the current, the under-toe of pulling people towards worrying about the wrong things. But all I can do is tell them what I know.”

We are back to the idea of Hawke as elder statesman, though of course he shows no signs of letting go of the baton yet. He is working now more than ever – he says he has to, with the decline of money in the indie film market: “It’s a lot harder to get paid to act than it used to be. The only thing you get paid for is a big studio movie. So you make hay when the sun is shining, or whatever that expression is. There’s a lot of good parts for me right now.” And he repeats his earlier confession, “Though I would have done Magnificent Seven for free.”

Nylon quilted peacoat DIOR HOMME

Comments